Suit-clad, sat at a v-shaped table arrangement in a

conference room in Holborn, discussing sustainability and the measurement of

social value, with representatives of the NHS, various media organisations, and

a sustainability certification company, I rambled my way through exercises with

marketing heads, mingled with big-wigs, and exhausted my resources of charm and

jargon-infused networking hot air.

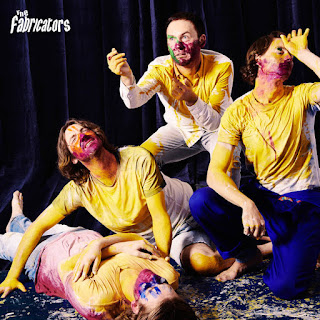

Seven hours later I was knelt down in a photographer's studio

in an industrial estate in the depths of Surrey Quays, head to toe in yellow,

purple, and orange paint, gesturing longingly in a renaissance painting style

pose towards a bandmate as if he was some kind of biblical figure, whilst a

fashion photographer barked orders at me.

I'm in a local band. This is the kind of thing that might

happen to you if you're in a local band.

Sometimes of an evening I will perform music that I have helped to create, to a room of people who have come out with the intention of being entertained. But by day I sit in an office and write about housing and the energy market.

It's a rewarding thing being in a local band, but it can also

be tough, and there's a lot of stuff that goes on that people don't see when

they are sipping their £5 can of average lager, as you struggle through your

new song. The kind of stuff that isn't the music stuff. The stuff that means

more people might hear the music stuff. Marketing I believe is the term people

are now using.

The problem is, from what I've gathered, it seems a band

breaking has a lot to do with luck and perseverance, and not really much else.

It's a process of feeding in a plethora of ideas into a confused machine, like

a 1995 PC that is still struggling with basic algorithms and spitting out

hopeful results. You never know what will come of these marketing ideas, but

you have to do them anyway. You have to type in the commands, in the hope that

something might happen, even if it's not exactly what you expected. Promoting

your band is often tireless, confusing, and very much hit and hope. Like the

game Minesweeper before you knew what the numbers meant.

And financially it's less like a 1995 PC and more like one of

those surprisingly enduring 2p machines you get at arcades and travelling

fairgrounds. You seem to be endlessly pumping money in, and eventually you

might get some back, but you're only going to pump it straight back in again,

with more money of your own, or money that you've just scabbed off your mate

Dave, who seems to have endless change. What you really want is the Tasmanian

Devil keyring hanging tantalisingly close to the edge. That's the breakthrough.

But it won't budge. It's possibly even glued down.

You're probably wondering when I'm going to let go of the

horribly dated metaphors. Well I'm not. Not for now at least. In terms of the

creative process, that's another thing entirely. I imagine if you were a

successful band with enough money for it to be your actual job and with people

employed to do all the admin and promotion, you could sit there all day

dreaming up the best lyrics and most iconic guitar riffs ever to be recorded

into a handheld recording device. But as I mentioned earlier, I spend eight

hours a day writing about housing and energy, concerning myself with whether

OPEC are going to extend their oil cuts to raise the market price. And when I'm

home I would rather have a can of Kronenbourg and watch Blue Planet again,

rather than write the next Stairway To Heaven, or even come up with a better

example of a great song than Stairway To fucking Heaven.

Which brings me to the aforementioned final (hopefully)

metaphor. James, my partner in songwriting crime once informed me that Paul

Weller compared songwriting to fishing. You may not catch anything for hours,

but you have to keep your rod in, and eventually something will come out. Which

is a fantastic metaphor, probably one of the best, but again, it applies mainly

to professional musicians with an established audience. It doesn't translate so

well to a man who only dips his rod in for a few minutes on his lunch break or

on the bus, searching for a deeply rounded lyric with tragi-comic undertones,

that will only be heard by a self-important sound guy and an Australian tourist

who's wandered into the wrong bar.

Moments of inspiration become all the more precious for the

local musician. You have less time to harvest it and a microscopic platform in

which to orate it. Even now, the ideas for this article have been snatched at

on a train between Thornton Heath and Wandsworth Common on my journey home from

work, my plight completely encapsulated by my attire: worn denim jacket and

charity shop jumper from which sprouts smart charcoal grey work trousers and a

pair of black shoes from Clarkes. I'm half a rockstar. Both spiritually and

aesthetically. I wear my juxtaposition as a uniform.

But this self-knowledge shouldn't stifle the creative

process, or so I tell myself. Even given the relatively small platform the band

has for its output, I still obsess over every nuance in every song. Every minor

vocal phrasing is vital. Every note matters. Because regardless of scale,

people do still hear it. If one person is at a gig, they deserve to hear us at

our best. If nobody is at a gig, at least we deserve to hear ourselves at our

best. Even now, despite being told that humans now only posses a mere 8 second

attention span, smaller than a goldfish, I still have the gall to try and

single-handedly bring back long-form journalism in a blog post which nobody is

still reading, understandably, particularly after the second abstruse metaphor.

Let me illustrate this with a real situation that happened to

me. Whilst in my previous band, we played a local music festival in Plymouth.

Our slot was around 13:00 on the first day. Not a great slot, so the only

people in the tent were the sound guy and four of our friends. Then, about

halfway through the gig, even our friends left, to find a bar to get a round of

drinks, leaving us playing to merely the sound guy. At that moment an actual

dog wandered into the tent. Then, for whatever reason, the sound guy left! So

for a good few minutes, as we were about to launch into an epic middle eight at

the peak of our set, we were literally playing to a dog.

Until this day I have never since played to an audience that

was 100% canine.

It makes me wonder. Did Prince ever rip out a mind-bending

solo to merely a German Shepherd. Or did Ian Curtis ever write what he thought

was to be his band's defining song, only to realise the lyrics were

unintentionally comprised of energy market similes?

I'd hazard a guess at no. The music industry at a worldwide

and especially at a local level is notoriously a lot less forgiving nowadays.

Sometimes it's enough to make you wonder why you bother. But the fact that I

still lug my guitar and pedal board around packed tube stations at rush hour,

more than anything, is proof itself that it must be worth doing. The rewards

are all the more rewarding as the hardship multiplies. The reward and toil are

one and the same. An appreciation of the absurd that Albert Camus' writing once

instilled in me, through a long-winded parable revolving around the myth of

Sisyphus, has enabled me to appreciate every part of the process. Bands have to

learn to love the rock which they are endlessly pushing up a hill, which in

this case is a sound guy deliberately trying to make your gigging experience as

uncomfortable as he possibly could without employing a team of people to

repeatedly mess with your tuning pegs throughout the gig.

And you know what? I enjoyed Minesweeper more when the

numbers were just blue and red nonsense designed to be ignored. That

unparalleled feeling of randomly selecting a little grey square that opened up

the entire mid section of the grid.

And what's more, I don't want the Tasmanian Devil keyring

anyway. Cos you can't feed a Tasmanian Devil keyring back into a 2p machine.

A few more things:

Some of my best lyrics were dreamt up between Thornton Heath

and Wandsworth Common train stations. In fact, some of the best lyrics ever

written were.

Energy market lexicon and music go together really well.

New songs should be struggled through.

Smart shoes, trousers, and a denim jacket is a good look.

Particularly for an older man.

I wouldn't have wanted to write Stairway To Heaven anyway. I

don't even like Stairway To Heaven.

And most importantly, even though it was only a dog, I like

to think it was having the best fucking time on its own watching my old band in

that tent. I could see it in that dog's eyes, as we surged into that key

change, lifting an already good song to the next level, a wall of shimmering

chords and a howling lead riff. I could see through its slobbering open mouthed

expression exactly what it was thinking. It was thinking:

“I know it's only 1pm on the Friday, but I'll be hard pushed

to top this over the course of the next few days. These guys are sick.”

The day after the EP cover shoot I sat there at work picking

yellow paint out of my beard, learning that Norwegian imported oil was short

that morning. But I did it with a smile, knowing that if nothing else, I'm a

weekend rockstar.

Mark Beckett

The Fabs first EP "Junction to the Jail" is out now on Ganbei Records, available to stream and download.

The Fabs first EP "Junction to the Jail" is out now on Ganbei Records, available to stream and download.